Andrew LaMar Hopkins

Andrew LaMar Hopkins (b. 1977, Mobile, AL) Andrew LaMar Hopkins is a singular voice in contemporary American painting, renowned for his meticulously detailed depictions of 18th- and 19th-century Southern interiors, architecture, and daily life. Deeply rooted in historical research, his work reconstructs the largely erased histories of Free Creoles of color, particularly in New Orleans, where he had lived for decades. Hopkins also maintains a studio space in Savannah, Georgia, and paints in Paris, France. Born in Mobile, Alabama, Hopkins grew up captivated by the Southern Antebellum Creole culture to which his family is intrinsically tied—a lineage tracing back to Nicolas Baudin, a Frenchman who received a Louisiana land grant in 1710. A self-taught artist and expert antiquarian, Hopkins channels his extensive knowledge of Creole material culture, architecture, and social history into paintings that are both historical documents and lyrical reimaginings. Visually, Hopkins’ compositions recall the folk traditions of Clementine Hunter, Grandma Moses, and Horace Pippin, yet his technical precision and layered storytelling distinguish his oeuvre. His works often depict the elegant interiors and street scenes of 1830s Creole port cities, rendered with exquisite attention to period details. In a radical departure from romanticized antebellum narratives, Hopkins introduces overtly homosocial or queer-coded elements, excavating the often-repressed histories of LGBTQ figures in the 19th-century South. His artistic practice is mirrored in his parallel persona as Désirée Joséphine Duplantier, a 1950s grande dame alter ego who embodies the theatrical, gender-fluid history of New Orleans. Hopkins’ work is internationally renowned, with features in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Garden & Gun, and Architectural Digest. His painting Self Portrait of the Artist as Désirée (2019) was acquired by the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., where the curator noted that it “significantly enhances our collection with its quality, rarity, and importance.” He recently concluded a year-long solo museum exhibition, Creole New Orleans Honey: The Art of Andrew LaMar Hopkins, at the Louisiana State Museum at the Cabildo in Jackson Square, accompanied by a dedicated publication of his work. On Hopkins’ rising influence in American art, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Jerry Saltz remarked: “People should see it.”

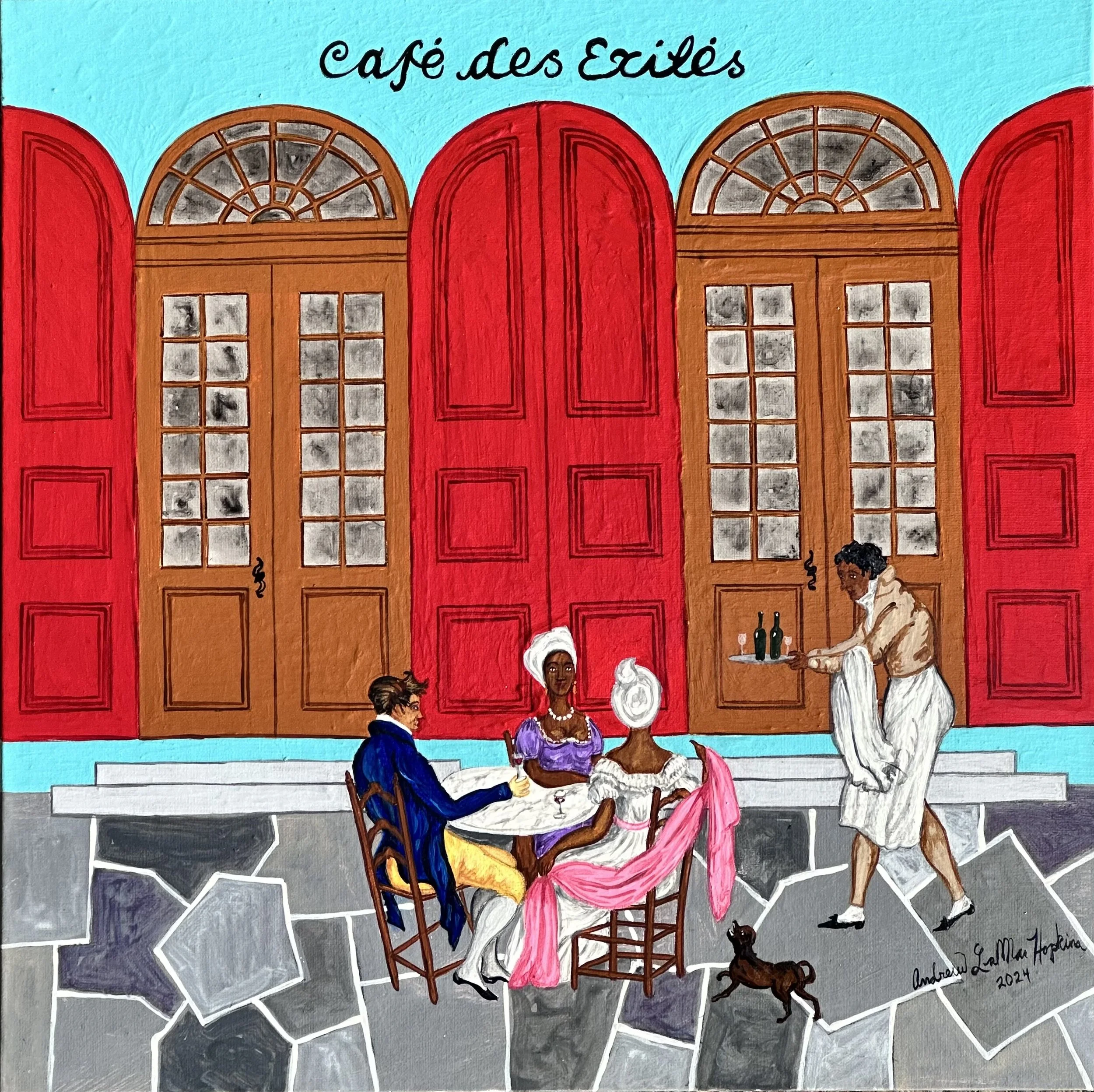

Café des Exilés

12 x 12 inches

This painting depicts Creole free people of color exiled from Haiti seated outside Café des Exilés”. In 1809, 9,000 people went to Louisiana from Haiti (it was close, people spoke French) — equal thirds white, free people of color, and slaves. This doubled the size of New Orleans. Café des Exilés was located on Rue Burgundy in the Old French Quarter. Opened by a Creole refugee from San Domingo. It was in an ancient Creole cottage sitting right down on the banquette, Creole word for sidewalk. The exiles from Haiti. Barbadoes, Martinique, San Domingo, and Cuba, sat their chairs out, sitting in their groups under the long, out-reaching eaves of the Creole cottage which shaded the banquette of the Rue Burgundy.

Grand-Mére Gris-Gris

9 x 12 inches

This painting depicts, a elderly Creole grandmother, Free woman of color street vendor seated on a New Orleans sidewalk with a basket of Gris-gris. She’s holding a palmetto fan in one hand and a bag of Gris-gris in the other. She is seated in front of a Greek revival house with pink stucco walls, where some of the stucco has fallen off showing the exposed brick building beneath with vegetation growing out. Next to her is a French olive jar. Gris-gris is a Voodoo amulet originating in West Africa which is believed to protect the wearer from evil or bring luck, and in some West African countries is used as a purported method of birth control. It consists of a small cloth bag, usually inscribed with verses from an ancestor and a ritual number of small objects, worn on the person. The practice of using gris-gris, though originating in West Africa, came to the United States with enslaved Africans and was quickly adopted by practitioners of Voodoo. Although in Haiti, gris-gris are thought to be a good amulet and are used as part of a widely practised religion; in the Creole/Cajun communities of Louisiana, gris-gris are thought to be a symbol of black magic and ill-fortune. Gris-Gris doctors have operated in the Creole communities of Louisiana for some centuries and are looked upon favourably by the community. In the 1800s, gris-gris was used interchangeably in Louisiana to mean both bewitch and in reference to the traditional amulet.

The Louisiana

Chinese Pagoda

16 x 12 inches

This painting depicts a Romantic Louisiana landscape with a beautiful Chinese pagoda tea house flanked by saucer magnolias and a free woman of color and a white creole gentleman. In front of the pagoda is a koi fountain with Chinoiseries polychrome lead fountain of a mandarin and dragon . Black and white Swans dot the landscape. The French have always had a passion for mixing Chinese/Chinoiseies decor, with traditional French design. And Louisiana Creoles were no different. 18th century Louisiana inventory list tapestries” with painted chinese figures, paintings with Chinese figures, Chinese lacquer furniture, Asian dressing glasses and trays, plus porcelain. In architecture country properties had garden Follies in the shape of Chinese Pagodas. Perhaps the best example of Chinese architecture in Antebellum Louisiana was a Chinese Pagoda built by Francois Gabriel Valcour Aime (1797-1867) at his famous plantation Le Petit Versailles. The Chinese pagoda Valcour built contained stained-glass windows and chiming bells. With grotto below the Pagoda!

Louisiana Axman

12 x 12 inches

The painting depicts a standing nude man holding an ax and wood in front of an elaborate trellised Garden wall. Flanking the standing nude is a pair of terra-cotta planters with pineapples and a Louisiana Great Egret.